Drugi jezik na kojem je dostupan ovaj članak: Bosnian

By: Adnan Arnautlija

How do we make choices – any choices, all choices? According to various sources, an average adult person makes 35,000 decisions every day, but are all those choices we make actually ours? Or were some of them made for us? And how does marketing industry tap into this decision making?

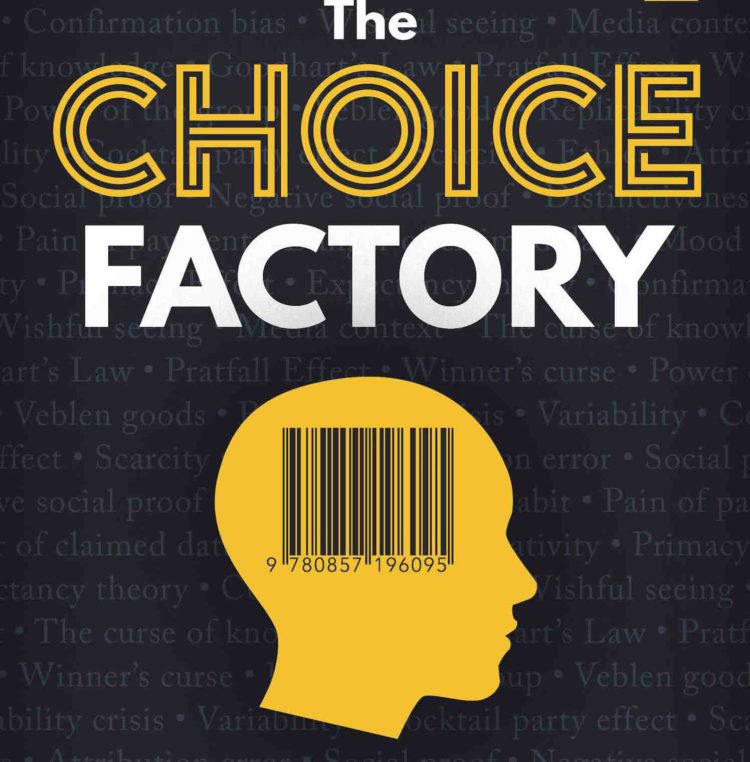

These are just some of the questions that came to mind when we received the new book The Choice Factory: 25 behavioural biases that influence what we buy, by Richard Shotton, Deputy Head of Evidence at Manning Gottlieb OMD. In the book, Richard brings us much closer to understanding how behavioural science leverages the mechanisms that influence our decision making, and shares tips and tricks that can help advertisers greatly boost the effectiveness of their campaigns.

You can find The Choice Factory on Amazon, and after going through the book, and seeing the great feedback from the industry, we warmly encourage you to get your hands on one, but until then, we picked Richard’s brain to find out more about the book, and how it came to be.

Media Marketing: First of all, why behavioural sciences?

Richard Shotton: There are three big reasons why marketers should care about behavioural science.

First, it’s the study of decision-making. Pretty relevant to marketing. After all, changing consumer decisions is at the heart of what you do, whether that’s persuading shoppers to switch to your brand, buy it more often, or pay a premium for it. All of it involves changing decisions.

Second, behavioural science is more than relevant, it’s also robust. It’s based on the experiments of leading scientists, such as the Nobel Laureates, Daniel Kahneman, Richard Thaler and Herbert Simon. Better to base marketing decisions on their experiments than the opinion of the most eloquent person in the board room.

Third, behavioural science has identified such a breadth of biases that whatever your client’s communication challenge, there’s a relevant bias to solve it.

Media Marketing: Influencing choices has always been the core purpose of marketing, but how much has changed from the behavioural science standpoint over time, due to technology advancement and other factors?

Richard Shotton: Marketers are obsessed with the latest fad. But human nature is remarkably consistent. Bill Bernbach, probably the most influential ad creative ever, summed it up best,

“It took millions of years for man’s instincts to develop. It will take millions more for them to even vary. It is fashionable to talk about changing man. A communicator must be concerned with unchanging man, with his obsessive drive to survive, to be admired, to succeed, to love, to take care of his own.”

The desire to demonstrate the consistency of our fundamental motivations was one of the main reasons I began conducting my own experiments. Over the last decade I’ve run hundreds of experiments and repeatedly shown that the insights discovered by psychologists as far back as the nineteenth century still apply today.

Media Marketing: In the book you dissect 25 choices made throughout the day, explaining them through what is called „classic bias“. How can marketers leverage these biases in their marketing efforts, and how should they choose what to focus on?

Richard Shotton: The best bit about behavioural science is that it is so practical. It’s not an abstract, academic discipline. It can help with all your marketing decisions from strategy to creative, media planning to pricing.

Let’s look at two examples in more depth. First, when to target people. Leon Festinger, the Stanford University psychology professor, has shown that rejecters of your brand are easier to persuade when they’re distracted. So this suggests a medium like radio, which is often listened to while people are busy doing other things, is better at converting rejecters than a medium that people give their full attention to, like print.

Second, understanding biases helps you know what message can best persuade your target audience. For example, most brands try and impress people by bragging about their strengths. However, experiments by Harvard psychologist Elliot Aronson, have shown that actually admitting your flaws can be a far better tactic. He showed that people who openly admit a flaw are far more appealing and I’ve shown that this finding works for brands too.

Some of the most successful brands ever have used this tactic to great effect. Just consider VW (Ugly is only skin deep), Guinness (Good things come to those who wait) and Listerine (The taste you hate twice a day). Three of the most successful campaigns of all time were built on a simple psychological insight.

Media Marketing: Can marketers actually make the choice for us as a consumer and how do ethics play into the whole concept?

Richard Shotton: Many people worry that behavioural science manipulates consumers.

However, let’s not exaggerate the impact of the discipline. The insights from behavioural science won’t sway everyone, all the time. They just increase the probability that communications have the desired effect. Nudges aren’t occult magic; they merely improve ad effectiveness through an understanding of how the mind works.

If we accept that nudges don’t bamboozle consumers, then what really is the complaint? That the communications are successful? Surely, if ads for a product are permitted, you can’t then object to them being effective?

As David Halpern, CEO of the Nudge Unit, says: “If we think it’s appropriate and acceptable for such communications to occur, it seems sensible to expect those designing or writing them to make them effective and easy to understand.”

And if it’s powerful communications that is being objected to, why single out behavioural science? Why not object to the great creative that has nothing to do with the discipline: the Cadbury Gorilla, the meerkat, or the 118 118 runners.

Advertisers have been trying to persuade people for hundreds of years. Behavioural science just helps them become that bit more effective.

Media Marketing: How did you go about the research for this book?

Richard Shotton: There are two elements to the research. First, I’ve read a huge number of psychology books and academic papers. I’ve then digested these findings and picked the 25 most relevant biases for marketers.

In the book, I explain those biases – from priming to the pratfall effect, from choice paralysis to charm pricing – in easy to read terms and, most importantly, explain how marketers can apply the findings to their work.

The second element is my own primary research. I have run hundreds of experiments over the last few years which look at how people actually behave, rather than how they claim to behave.

An example of this approach was for a clothes shop, New Look, who were due to launch a menswear range. Their initial plans were to put a small budget behind a simple announcement.

I suspected this wouldn’t overcome men’s reluctance to buy clothes from what was perceived as a women’s clothes shop. However, that was a hunch and we had no budget to fund a survey.

As an alternative, Dylan Griffiths and I recruited half a dozen men and photographed them twice: first holding a New Look plastic bag emblazoned with their logo, then one while holding a Topman bag. We uploaded the images to a dating site where people rate the looks of other users’ photos. The pictures were left up on the site for two weeks while we waited for them to be rated.

We found that when our volunteers were holding a New Look bag they were rated as 25% less sexy than when they were clutching the Topman bag. This demonstrated that the brand had a bigger task than they had initially suspected, and that they needed to redouble their efforts to persuade men that they were a unisex brand.

The benefit of this technique was that we quickly and cost-efficiently found out what people genuinely thought about the brand when they didn’t know anyone was watching.

Media Marketing: Could you give one example of a marketer or campaign that has succeeded in making the choice for us?

Richard Shotton: One of my favourite examples of a brand making the choice for us stretches back eighty years. Back in the 1930s there was no tradition of buying diamond engagement rings: sapphires, emeralds and rubies were just as popular.

But that all changed with perhaps the most effective campaign of all time: De Beers diamonds. First, De Beers linked a diamond’s durability with the enduring nature of true love. They did this with a wonderful strapline, written in 1947 by Frances Gerety, “A diamond is forever”.

However, once De Beers had established that a diamond was the ideal choice for an engagement ring, they still had to convince buyers to spend heavily. To do this, they communicated the idea that nothing less than a month’s salary would do.

Surely, that’s laughable. Why believe a salesman who has a vested interest in you spending heavily? But the ploy worked, not just because of memorable copywriting, but because of a psychological principle called anchoring.

Anchoring is the idea that if you communicate a number, however spurious, it influences the listener. The bias, discovered by two psychologists, Kahneman and Tversky, believed that anchoring works because listeners inadvertently use any arbitrary number as a starting point for their deliberations. Crucially, even if the listener recognises that the number is irrelevant they don’t adjust enough away from the anchor.

So, ring buyers recognised that a month’s salary was a touch on the expensive side, but it served as a starting place for their deliberations and they failed to adjust down enough.

The results were staggering. Not only did diamonds become the default choice, people were prepared to spend lavishly. De Beers US diamond sales rose from $23m in 1939 to $2.1bn in 1979. Even accounting for inflation that’s a nineteen-fold increase.

The approach was so successful that in the 1980s De Beers updated their advice. They began suggesting that people should pay two months’ salary for a ring. Again, people recognised that sum was too much, but the number acted as an anchor and they spent more.

Then in the 1980s, De Beers launched in Japan where there was no heritage of diamond ring buying. They suggested that spending anything less than 3 months’ salary was stingy! Once again, the amount spent on diamond rings increased.